Culture Posts: Individualism, Collectivism – and Relationalism

February 10, 2013 § 8 Comments

In honor of the New Year (both West and East), I would like to share a relatively new lens for viewing relations in public diplomacy. Many may have heard of the terms individualism, which privileges the individual, andcollectivism, which favors the collective or group. What they may not have heard about yet is relationalism, which privileges personal relations. At the time of this writing, relationalism literally “isn’t in the dictionary” – at least the most prominent one in the English-language.

Relationalism is in Wikipedia. However, the entry lacks cultural and communication dimensions as well as the pivotal contributions from female and Asian scholars.

For public diplomacy, relationalism offers a more refined lens for viewing relationships beyond simply “one versus the many” or “two-way communication.” Relationalism may be particularly valuable for understanding the dynamics of networking and collaborative public diplomacy.

Opposing Cultural Perspectives: Individualism & Collectivism

Both individualism and collectivism are in the dictionary. Individualism is of British origin, stemming from the works of Adam Smith and Jeremy Bentham, according to Merriam-Webster. However, Alexis de Tocqueville is often credited with coining the term during his visit to America in 1831. He was trying to describe the American spirit and what distinguished the “new world.” “Individualism is a novel expression, to which a novel idea has given birth,” wrote de Tocqueville. That novel idea was self-reliance, independence, equality, and personal freedom. De Tocqueville entitled his book Democracy in America.

Individualism has been an enduring part of American parlance, and favorably so, given its association with democracy. Perhaps, not surprisingly, collectivism has been less well understood. When contrasted against individualism, the depictions are often less flattering and even antagonistic. Whether it is fighting communists during the Cold War or resisting Borg on Star Trek, the collective is often presented as a threat and even mortal enemy of the individual.

In scholarship, the idea of individualism/collectivism dates back to 1953 and Florence Kluckhohn’s “value orientations.” She described the nuclear family as an individualistic, the extended family as collateral, and the inclusion of ancestors to the family sphere as lineal.

Individualism and collectivism was one of the five dimensions proposed by Dutch social psychologist Geert Hofstede in his landmark study Culture’s Consequence (1980). Hofstede, who was working with IBM at the time, came across a treasure trove of data from different IBM groups in more than 50 countries. He speaks of national cultures and positions countries relative to each other. Hofstede said that individualism prevails in “developed and Western countries,” while collectivism prevails in “less developed and Eastern countries.”

Hofstede often contrasts individualism and collectivism. Features of individualism include: “I”- consciousness; People take care of themselves and immediate family only; Speaking one’s mind is healthy; Personal opinion expected; Others classified as individuals; and Task prevails over relationships.

Features of collectivism include: “We” consciousness; People are born into extended families which protect them in exchange for loyalty; Harmony should always be maintained; Opinions are predetermined by in-group; Others are classified as in-group and out-group; and Relationship prevails over task.

Another social psychologist, Prof. Harry C. Traindis of the University of Illinois also wrote extensively on individualism/collectivism. Traindis focused at the individual or personal level. With the help of his doctoral student, C. Harry Hui, he refined the framework. [1]

Their research highlighted how relationships differ. Individualists tend to value independence and autonomy and favor relationships that are egalitarian and horizontal, such as friendships or marriage. Because the goals of the individual take precedence over the group goals, relations are often voluntary and temporary.

Traindis said collectivism tends to value interdependence and privilege vertical relations such as parent-child, each with different roles and obligations. Relations are often involuntary and long-term. Individuals are willing to forgo personal goals if they conflict with group goals. Distinctions between “in-groups” and “out-groups” are clearly defined. While collectivism strongly encourages cooperation within the in-group, out-groups are looked on with suspicion.

Individualistic Japanese & Collectivist Americans

The individualism-collectivism dimension has been one the most prominent cross-cultural tools within the social sciences. It has been used to analyze cultural differences across a range of phenomena, from advertising appeals to management styles and negotiating strategies.

Part of the dimension’s appeal is its simplicity in providing a powerful explanation for behavioral differences around the world. The individualism-collectivism dimension remains popular. However, scholars who have surveyed the mass of studies over the past three decades are raising red flags.

A team of social psychologists led by Daphna Oyserman at the University of Michigan surveyed studies published between 1980 (the year Hofstede’s book appeared) and 2000. [2] They wanted to see if Americans were the “gold standard” of individualism.

What the scholars found was rather surprising: Americans were no less collectivist than Latin Americans and some Asians. Several studies showed the Americans were more collectivist than the Japanese. The only consistent and robust difference in collectivism was between the Americans and Chinese.

Oyserman and her colleagues blamed the unexpected variations on the different measurement scales. Researchers appeared to have different ideas about what constituted individualism and collectivism.

Even before these literature reviews, other researchers using the same scale found similar anomalies. Triandis’s own research team had to re-think their assumptions. The scholars expected Americans and European to be highly individualistic and Latin Americans and Asians highly collectivist. That was not what they found: “In fact, the “highest score on interdependence was from the Illinois females!” Exclamation point is theirs.

It was not just Triandis who had found American women to be the relational outliers. One of the first studies on collectivism noted a similar gender difference.[3] Another team of researchers in 1995, found that females across five cultures – America, Australia, Hawaii, Korea and Japan — were all more relationally oriented than their male counterparts.[4]

Scholars also raised flags about the long-held assumptions about group biases. Individualists were also assumed to not make in-group / out-group distinctions. That is a trait of collectivists. Yet, the actual studies revealed that loyalty to the in-group and suspicion of out-groups were just as pronounced, if not more so, in Western cultures than in Asian cultures. [5]

In-group favoritism and out-group suspicion does not seem as shocking when one considers the history of racism and segregation in America, or European colonialism, the Holocaust, and even the current debates over immigration and signs of Islamaphobia in Europe and America. Upon reflection, individualist Americans’ and Europeans’ history of in-group and out-group distinctions seems curiously overlooked.

With the many inconsistencies, one team of scholars suggested that collectivism is a “misnomer.”

The reality may be, as several scholars have suggested, that every society contains elements of individualism and collectivism in order to meet the demands and complexity of social systems.

A Third Dimension

It was not just that individualists were becoming collectivists, or globalism was transforming collectivists into individualists. A growing number of researchers began to suspect there was another dimension. Researchers had overlooked an entire layer of relations.

In the next Culture Post, I will look at some of the research and thinking that fostered the emergence of relationalism and relationalism’s implications for public diplomacy.

FROM Culture Posts series

Zaharna, R. S. (January 28, 2013 ). “Culture Posts: Individualism, Collectivism — and Relationalism,” in USC Center on Public Diplomacy, Blog Series

- C. Harry Hui and Harry C. Triandis (1986), “Individualism-Collectivism: A Study of Cross-Cultural Researchers,” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 17(2): 225-248

- Daphna Oyserman, Heather M. Coon, and Markus Kemmelmeier (2002), “Rethinking Individualism and Collectivism: Evaluation of Theoretical Assumptions and Meta-Analyses,” Psychological Bulletin 128 (1), 3-72.

- Kwok Leung and Michael H. Bond (1984), “The Impact of Cultural Collectivism on Reward Allocation,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47 (4): 793-804.

- Yoshihisa Kashima, Susumu Yamaguchi, Uichol Kim, Sang-Chin Choi, Michele Gelfand, Masaki Yuki (1995). “Culture, Gender, and Self: A Perspective From Individualism-Collectivism Research,” Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 69(5):925-937.

- Marilynn Brewer and Ya-Ru Chen (2007), “Where (Who) Are Collectives in Collectivism? Toward Conceptual Clarification of Individualism and Collectivism,” Psychological Review, 114 (1): 133-151.

The 4th Quadrant of Public Diplomacy

February 9, 2013 § 5 Comments

Nation states are facing a second wake-up call in public diplomacy. The first wake up call, prompted by the 9/11 attacks, was the realization that perceptions of foreign publics have domestic consequences. The second wake up call, which rang out first for China during the 2008 Olympics, and then for other countries with Wikileaks, the Arab Spring, and the Occupy Movement, is that adversarial publics are able to challenge states in the quest for global public support. How states can effectively respond to this second wake-up call is a pressing area of public diplomacy research.

States appear to be viewing public diplomacy through a geopolitical lens and are focusing on other states as their primary competitors. However, viewed through a strategic communication lens, the greatest PD competition and threat to states are not other states, but rather initiatives by adversarial publics. Aside from challenging individual states, the diversity of political perspectives and cultural identities of these publics raise questions about whose ‘norms’ and ‘rules’ should govern how issues are addressed in the global public arena. This has implications for all states.

To begin to address this challenge, public diplomacy needs a more nuanced understanding of publics beyond non-state actors. The international relations (IR) literature tend to use the terms “state-based” and “state-centric” interchangeably to distinguish domains of state actors from non-state actors. In communication, the term “audience-centric” is used specifically to distinguish between communication messages and approaches designed around the audience’s needs, interests and goals and those of the sponsor. Whereas much of PD has highlighted (soft) power, messages, or images, the PD Quadrants below highlight the importance of the relational dimension between states and publics in considering strategic PD options.

State-based Public Diplomacy

PD Quadrant I reflects the traditional view of public diplomacy as a state-based, state-centric activity. It is state-based in that the initiative is designed, implemented and controlled by the state. It is state-centric in that PD initiatives are designed to meet the interests, needs and goals of the state. Relations with publics are often obscured by the focus on getting the message out and promoting the state’s interests. Because the public is viewed as passive, the relational dimension is often unexplored. However, if relations are positive, the message and image of the state tends to be favorably received. If relations are negative, the state’s communication efforts tend to encounter unexpected resistance. International broadcast and nation branding campaigns reflect the state-based, state-centric public diplomacy of PD Quadrant I.

PD Quadrant II represents a shift from state-centric to public-centric initiatives. Initiatives are still state-based in the sense that it is the state that initiates, sponsors the initiative. However, despite state control over the initiative, public participation and building positive relations is viewed as pivotal feature for PD initiatives in PD Quadrant II. To secure public participation and build relations, rather than being primarily focused on the state-centric needs or goals, the PD initiative’s message, approach and selection of media platforms are designed to resonate positively with the public. The rise of the “new public diplomacy” over the past decade that advocate a more “relational” approach and the view of public diplomacy as “engagement” exemplify the state-based, public-centric initiatives in PD Quadrant II.

Reversing the Role of the Public

PD Quadrant III represents a shift from state-based to public-based initiative. Digital media have effectively enable publics to reverse communication roles with the state. Rather than being a consumer of state-generated information, publics are able to generate communication for state attention and consumption. Whereas the state-based, public-centric initiatives in PD Quadrant II seek to co-opt the public, the public-based, state-centric projects in PD Quadrant III seek to co-opt and involve the state. Many of the global, complex issues such as global warming, health, and education originally launched by public such as the Campaign to Ban Landmines, are illustrative of PD Quadrant III.

What both PD Quadrant II and III have in common is a neutral to positive relations between state and publics. Publics are often called “stakeholders,” and assume organized public representatives such as civil societies or nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). There is also an implicit assumption that the state and the public share similar goals and perspectives. The positive relations and shared perspectives lie behind the willingness to adapt messages and approaches, build relations or networks, seek commonality, mutual engagement, dialogue, and potential collaboration.

Adversarial Public Stakeholders

PD Quadrant IV is distinguished from other quadrants by the public’s capacity to produce PD content neutral to negative relations with the state. PD initiatives are public-based in the sense that the public retains primary if not exclusive control over the initiative. The initiatives are public-centered in that they are designed to meet the needs, interest and goals of the public, which may be framed as neutral or counter to those of the state. Rather than assuming positive relations with publics, states may be faced with adversarial public stakeholders. While often overlooked, these public stakeholders may be even more strategic stakeholders in public diplomacy initiatives.

Because adversarial stakeholders continue to retain a strong vested interest in a contested public issue, they cannot be dropped from the PD equation even if they disagree with the state. Nor can they be dismissed as “irrational.” These adversarial stakeholders may command more perceived credibility and legitimacy by the public than the state. Attempts to openly challenge these stakeholders can further serve to alienate the state. The state may struggle for relevancy. Most importantly, these stakeholders are proving adept at using digital tools and network communication strategies to generate a soft power differential capable of challenging states. They can command state attention.

For states, PD Quadrant IV represents the challenge of “crisis public diplomacy.” Unlike the relatively stable communication with benign publics, crisis public diplomacy entails communicating simultaneously with multiple publics – not just foreign or domestic, but favorable and adversarial publics – in a highly visible, rapidly evolving, contested public arena.

Whither Public Diplomacy?

In theory, if not entirely yet in practice, states have gotten the first wake up call. The need to shift from state-centric to more participatory and relational public-centric approaches is evident in the accelerated use of social media in public diplomacy.

States may be less appreciative of the full implications of the second wake-up call, or shift from state-based to public-based initiatives. Recent PD reports reflect the trend of discussing public diplomacy in terms of (soft power) competition from other countries. However, the majority of the threats raised in the reports are not from other countries, but from adversarial public stakeholders in PD Quadrant IV.

In looking ahead to the future of public diplomacy, states need to move quickly beyond whether and how to use the social media for public-centric initiatives. As mentioned in the soft power differential, the greatest potential threat that states face is being blind-sided by a highly-network non-state actor. Already this has happened for several states. Understanding the dynamics and developing strategies for adversarial public-based PD Quadrant IV is one of the most urgent and pressing area of public diplomacy scholarship.

FROM Culture Posts series:

Zaharna, R. S. (November 6, 2012). “The 4th Quadrant of Public Diplomacy,” in USC Center on Public Diplomacy, Blog Series

Culture Posts: Giving Voice to Publics

February 9, 2013 § 18 Comments

Last week, before the world caught on fire over a film clip, I wrote about the paradox of value promotion in public diplomacy. No matter how appealing promoting one’s values may be, trying to do so in a global arena is fraught with difficulty. Yet, because values are integral to a nation’s communication, public diplomacy will inevitably reflect those values. What’s happening between the U.S. and publics in the Islamic world reflects the immediate consequence of the paradox of value promotion – both sides are trying to communicate what they value, but rather than being understood – they are less so.

The more they persist in their efforts, the more likely the cycle may escalate. In the long term, a battle over value promotion is a no-win scenario in today’s global communication arena. To be savvy, public diplomacy strategists need to find ways to give voice and bring the public into the public diplomacy equation.

Value Contests

Let me speak first to the immediate term, then the long term, of trying to play out value contests.

In the short term, value promotion can cause more misunderstanding rather than less. Greater misunderstanding often leads to greater frustration. Unresolved frustration often leads to anger. That’s the chain.

There is also the communication chain. When people become frustrated that their verbal efforts to communicate aren’t working, they often resort to more disparate physical means.

The chains explain how anger develops, but they do not justify violence – physical, verbal, or visual. It is important to recognize that verbal and visual violence can be as damaging to human spirit as physical violence is to the life and limb. Verbal assaults that strike the soul can take longer to heal than physical ones. Images seared in the mind are difficult to erase, if ever.

While anger may be the emotion, violence does not have to be the inevitable or the only avenue of expression.

Digital Protest Venues

An immediate short term step that an entity can do in a crisis situation is to try to create public communication channels for publics to express strong emotion – confusion, discontent, anger. This strategy of capturing and trying to diffuse hostile public sentiment was done in several domestic U.S. crises by using the social media. One technique was setting up a ‘gripe’ Facebook page. A similar strategy was used in Singapore: the very same social media tools that had been used to spark the public outrage were used to capture and contain that outrage.

Here is where U.S. public diplomacy must be creative and innovative in adapting its expertise in social media. Rather than using the tools to get the U.S. message out, the tools are creatively used to give others a voice.

Philip Seib, in a personal email, put a nice label on this strategy: it is “providing electronic protest venues.”

Naturally, there will be those whose interests are in promoting violence, not quelling it. However, physical forms of communication are costly. Most people seeking communication want to be heard and understood. By creating a credible a space or forum for verbal expression, the need or justification for physical expression becomes less pressing and others are less able to exploit public sentiment.

The need to give voice is not just an immediate short term strategy. Creating channels for publics to communicate — or speak to power – is especially important for a superpower.

A Second Wakeup Call

Since 9/11, much of public diplomacy has focused on how nations can get their messages out–how to strengthen their voices. Engagement and networks are more efficient strategies for communicating to or with publics.

If 9/11 was a wakeup call for state-centric public diplomacy; the events by publics over the past couple of years should be a second wakeup call to explore the public role in public diplomacy. Publics are participatory. They are networked. They are increasingly communication savvy.

Strategic public diplomacy is no longer communicating to or even with publics. It is integrating communication from publics.

For the U.S., as a superpower, it is not about “being heard,” but about giving voice to those who feel they are not. The U.S. may lament that it is not understood and feel compelled to work harder and shout louder.

But much of humanity across the globe shares that frustration of not being understood and wants to shout louder. Yet, unlike the U.S. government, they do not have the means or resources. That imbalance of communication power further fuels frustration.

Building bridges in an interconnected world represents a mindshift in thinking from “mutual interests” to “mutuality” as the basis of global communication. The tendency is to look for mutual interests and benefits – finding what two parties have in common. If there is nothing in common, the one without power loses. “Mutuality,” as outlined in a British Council report, is unconditional recognition of the needs of the other. Kathy Fitzpatrick also wrote about “mutuality” in her CPD fellowship.

To be effective in a connected network world, the U.S. as a superpower needs to shift its perspective from thinking of “mutual interests and benefits” with equally powerful players to “mutuality” and adjusting its power with less powerful players. We live in an interconnected world. The publics around the world have seized on the reality. Adopting the mindset of mutuality will help ease the communication tensions and create communication bridges instead of battles.

FROM Culture Post series:

Zaharna, R. S. (September 18, 2012). “Culture Posts: Giving Voice to Publics,” in USC Center on Public Diplomacy, Blog Series

Culture Posts: Paradox of Promoting Values

February 9, 2013 § 6 Comments

I have always been intrigued by the desire of countries to convey their cultural, political or social values as part of their public diplomacy mission. On the surface, it is appealing. However, in practice, it is fraught with challenges and is something of a paradox.

On the one hand, it is difficult to accurately convey cultural values because they are so deeply tied to a country’s historical and socio-cultural experience. Something gets lost in the translation. However, because values are so integral to a nation’s experience and identity, a nation’s communication will inevitably convey something of its values.

Appeal of Values

The appeal of values as a persuasive tool dates back to Aristotle’s Rhetoric in the Western intellectual heritage. Implicit in Confucius’ The Analects are values that govern behaviors and proper relations in society. Contemporary persuasion theories provide strong support for using values to change attitudes and behavior.

Post 9/11 U.S. public diplomacy highlighted values as a strategic cornerstone in its public diplomacy.

The first priority of US public diplomacy is “to inform the international world swiftly and accurately about the policies of the US government,” and then, “re-present the values and beliefs of the people of America, which inform our policies and practices.”

Charolette Beers

People who share similar values often feel greater attraction to each other and experience more ease in communicating with each other. Similarity and ease in communication and understanding may also fuel public diplomacy use of values.

Values as Abstract

While the desire to use values may be appealing, the challenge of effectively doing so may be daunting. Values are abstract nouns of culture — and that public diplomacy is inherently intercultural.

Unlike concrete nouns or objects, abstract noun do not exist in reality per se – but in our minds and even hearts. This privilege location can heighten their significance in public diplomacy.

Values are abstract or intangible in the sense that one cannot physically touch them. How do you communicate values such as “generosity” or “discipline” so that it is understood by global publics with different value schema? To give lavishly or more than is expected may be interpreted as “wasteful” by others who value “frugalness.” Pride in self-discipline and controlling one’s urges may be perceived as “rigid” by others who value “spontaneity.”

Nation branding campaigns often try to convey of cherished values. Thailand, known as the “Land of 1000 Smiles,” communicated their treasured value using slight variations of related words to appeal to different audience: “joy” and images of shopping bargains for Asian tourists and “bliss” and tranquil beaches to lure European vacationers.

Multiple Interpretations

Because values exist in the minds of people, values can have different meanings and manifestations. Two people with different value schemas – priorities and understandings – can look at the same object and see two different things. And feel very strongly about what they see – and don’t see. The 2005 caricatures of the Muslim prophet in a Danish newspaper were simultaneous perceived as “freedom of speech” and “blasphemy.”

While values may be abstract in theory, the manifestations of cherished values are often perceived as very real and concrete to their owners. People may rise up to protect values, beliefs, and traditions as if they were a physical entity.

Given these features of abstract nouns – invisible, yet powerful – public diplomacy officials need to be particularly alert to two major hurdles.

Selective Attention

Most public diplomacy initiatives are laced with numerous values. PD officials may design initiatives to highlight a particular value only to have audiences focus on something entirely different and even unexpected.

For example, China as the official host of the 2008 Olympics took great efforts to prepare its domestic public to properly receive the expected crowds of foreign visitors. The people were described as the keys to success. The government distributed a brochure for protecting the national image and included guidelines on proper manners and dress. Such attention to detail, especially in hosting guests, is a hallmark of relational finesse and exemplary of the value of propriety in relations.

Selective attention – Not all values are prioritized the same. Global audiences will tend to attend to the value that is important for them – which may not be the same value of the public diplomacy planners.

This attention to relational detail in receiving visitors was not the dominant value for global, especially Western audiences. Global audiences will tend to attend to the value that is important for them – which may not be the same value of the public diplomacy planners.

Selective Perception

Second, there is the concern of selective perception. Even if one is successful in focusing attention on a particular value, the audience may have a different understanding of that value.

Having a “voice” in democracy may mean the act of voting. To others, it may mean being consulted in a deliberative, consensus-building process. Similarly, “empowerment” may be seen at the individual-level, such as empowering individual women entrepreneurs; or, at the group-level, such as empowering the role of women in society, or women’s organization.

Selective perception — A value may be universal, but its expression may not. Different cultural contexts often have different cues for expressing and interpreting a value.

There may be merit in suggesting that values are “universal.” However, in practice, their expression may not. Anne-Marie Slaughter suggested tolerance was universal in her book, “The Idea that is America: Keeping Faith with Our Values in a Dangerous World.”

Two students in Singapore, one Asian and the other American, reviewed her book. The students debated Asian and Western values and the idea of universal values. They turned, as example, to the value of tolerance. The students discovered difference in perception of the role of listening and speaking in how “tolerance” is expressed and manifest in the American and Chinese perspectives. They concluded: “The virtue of tolerance is universal like the other values in this [Slaughter’s] book. Yet the approaches to tolerance may be defined differently in diverse cultural contexts.”

Value Paradox: Ideals, Interests and Credibility

The paradox of values in public diplomacy is that while nations struggle to convey their values, most communication by any person or entity reflects its values — whether the person deliberately intends so or not. And, this paradox raises other challenges for public diplomacy.

There is no “down time” in public diplomacy: nations cannot not communicate their values. Publics are constantly looking for what they perceived as “the true values” of a nation in its words, actions and policies.

First, there is the challenge of values as ideals. Values represent the ideal of what people aspire to rather than what or who they actually are. It is difficult for individuals to live up to their ideals. It is perhaps even more so for nations to meet those standards. Yet once those values are expressed and promoted, the nation provides global audiences with a yardstick for measuring its actions and policies. A perceived gap between promoting a value as an ideal, and demonstrating that value as a reality, may erode a nation’s credibility. The more visible a nation, the more likely global audiences will scrutinize discrepancies between promoted value and lived value.

Second, there is the challenge of perception. There is no “down time” in public diplomacy: nations and their officials cannot not communicate their values. However, just as publics use selective attention and selective perception in planned public diplomacy initiatives, so they will likely do so in unplanned incidents. Trying to control misperceptions may be futile. Anticipating and adjusting misperceptions may be more fruitful.

Third, there is the challenge of national value and national interest. Not all the problems are about perception. Some are political. When professed national values conflict with actions based on national interests – and publics spot the contradiction – there will be a public diplomacy cost. Human failings that result in a lapse between “ideal” and “real” may be excusable and even lauded by some who value trying. However, publics may be less forgiving for deliberate aberrations between political word and deed.

Public Diplomacy Implications

For planned public diplomacy initiatives:

- Consider other possible values buried in a PD initiative, not just the particular value that is being promoted.

- Explore how a value may have different meanings, expressions and manifestations in different settings.

- Pre-test value-laden programs with culturally diverse audiences.

For un-planned public diplomacy incidents:

- Stop and try to assess differences in value schema that may be contributing to differences in perceptions.

- Look for ways to address the differences on multiple levels, including symbolic and indirect acknowledgements.

- Develop a “value radar” for greater self-awareness and other-awareness to anticipate and accommodate differences in the priorities and expression of values.

FROM Culture Posts series:

Zaharna, R. S. (September 10, 2012). “Culture Posts: Paradox of Promoting Values,” in USC Center on Public Diplomacy, Blog Series

Culture Posts: A New Frame – The U.S. Public Diplomacy Act of 2014

February 9, 2013 § 2 Comments

It is the summer of 2012 and America is debating whether to modernize a piece of 1948 legislation on U.S. public diplomacy called the Smith-Mundt Act. At a time when American officials are racing to keep pace with the new communication technologies and trying to “out-communicate” the terrorists, not just other nations, the whole debate is mind-boggling. Ultimately, the debate is about much more than the legislation and speaks volumes about America understanding of communication in a global era. To get up to speed, U.S. public diplomacy needs the U.S. public, and both need a U.S. Public Diplomacy Act as soon as possible.

A Potentially Dead-In Debate

Yesterday’s analysis of the Smith-Mundt Modernization Actrevealed a battle between two iconic American values. In one corner: “modernization” and the appeal of the future. In the corner: “propaganda” and the threat to individual freedom. So long as these two values remain pitted against each other, the legislation floating on the surface will continue to draw fire from across the political spectrum. At stake are treasured American values. U.S. public diplomacy is caught in cross fire.

The longer the debate continues, the more likely the two competing frames will become entrenched. Already, the battle has moved to the social media, Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn. As mentioned in a previous post, and quoting Alec Ross, “the social media reward the extremes.”

Unfortunately, or fortunately, any reference to “Smith-Mundt” is likely to trigger a repeat of the propaganda-public diplomacy debate. Not surprisingly, two years ago there was such an attempt and it didn’t get far. What’s needed is a fresh start in how the public, officials, and policy makers think about U.S. public diplomacy – which is a good thing.

New Tools: Media Literacy

Many have suggested the Smith-Mundt battle is generational. Actually, it may be more a matter of education and training. What the younger bloggers share with some of the beyond twenty-something bloggers trying to put propaganda in perspective, is formal study of persuasive tactics and media literacy. Learning how to read, analyze and create media content has become as critical as learning grammar. It begins in elementary school now.

The fear of propaganda harkens back to an era when persuasion was a new field of study. Mass media was the “new” media. Both were little understood and perceived as all powerful. Over the years, persuasion strategies have grown increasingly sophisticated. Compared with advanced stealth tactics, propaganda’s one-way “information dissemination” mode probably ranks a 2.4 out of 10 on Richter scale of persuasion. While persuasion strategies today are more sophisticated, so too is the audience. Media literacy and constant exposure to persuasion have made the public, especially the youth, not only savvy consumers of persuasion but producers as well. From the Arab Spring to Anonymous, the communication tables are turning between publics and governments. It’s not just social media. It’s media literacy.

New Mindset, New Frame

If one thing has become increasingly clear from the debate it is the lack of understanding about the critical role of U.S. public diplomacy – and the role of the U.S. public in U.S. public diplomacy. U.S. public diplomacy needs not just a new amendment, it needs a new mindset. With that mindset lays the promises of a new U.S. Public Diplomacy Act.

1. Think Global Communication: Global technology & Global publics

The first feature of the new mindset and goal of the U.S. Public Diplomacy Act is to think globally. Currently, on several levels, U.S. public diplomacy is defined in national and even inter-national terms. Perhaps a short decade ago, it was possible to think about communication in those terms. With today’s advanced communication technologies, there is no longer a domestic public or even truly foreign publics; but rather one global public. What one hears; they all hear albeit differently. The challenge is not how to separate the two; but how to speak to so many simultaneously. Remember also, that global public is constantly on the move. Global migration means thinking of audiences in terms of media platforms rather national territories.

2. Think Monitoring and Transparency

A second feature of the new mindset and goal of the U.S. Public Diplomacy Act is monitoring and transparency. Not only is the communication environment global, it is highly competitive. U.S. public diplomacy may be the leader in the field, but it is not the only player. Numerous countries have established television programming and cultural programs specifically for the U.S. public. There is Qatar’s Al-Jazeera, BBC’s UK-USA and Russia’s Russia Today. If China’s CCTV has not been as successful, its Confucius Institutes are. Where is U.S. public diplomacy in this line up?

Rather than keeping the U.S. public in the dark about official U.S. communication activities, U.S. public diplomacy needs more exposure and transparency. First, for those who worry about U.S. government takeover of the American people, unfettered access to U.S. public diplomacy is exactly what’s needed to monitor it and make sure it doesn’t get out of control. Helle Dale of the Heritage Foundation picked up on this point early. It needs underscoring. Second, U.S. public diplomacy could benefit from domestic feedback, especially from one as ethnically diverse as the American public. Other countries have been quick to appreciate the importance of not only their domestic public but their diaspora in the global communication equation.

3. Think Collaborative Diplomacy and Citizen Diplomacy

A third feature of the new mindset and goal of the U.S. Public Diplomacy Act is moving from the old public diplomacy to the new public diplomacy. Once upon a time it was enough to craft messages and shoot them into stationary target audiences. It worked once. It doesn’t now. Governments are no longer the only players competing against each other. And radical activists rarely play by the rules. Soft power is transforming into what Anne Marie Slaughter called “collaborative power.” Public diplomacy is becoming more networked, more collaborative public diplomacy.

To be effective or even stand a chance in such a dynamic communication arena U.S. public diplomacy needs an expanded vision beyond its official itself. The U.S. public needs a voice in the conversation that is U.S. public diplomacy.

Already, the U.S. public is trying to be more involved. Witness the thrivingcitizen diplomacy and public-private partnerships. They are mushrooming across the nation. In one of her first statements, the new Under Secretary of State Tara Sonenshine spoke of the link between people, policy and U.S. public diplomacy. Citizen diplomacy along with collaborative public diplomacy exemplifies the new vision of U.S. public diplomacy.

More than ever, the U.S. public needs effective U.S. public diplomacy. And, more than ever, U.S. public diplomacy needs the U.S. public. Rather than competing against each other, both can embrace the challenge of change and innovation in a new U.S. Public Diplomacy Act of 2014. That is, if it can be achieved sooner.

FROM Culture Post Series:

Zaharna, R. S. (June 7, 2012). “Culture Posts: A New Frame – The U.S. Public Diplomacy Act of 2014,” in USC Center on Public Diplomacy, Blog Series

Culture Posts: Exposing The Battle of US Values in the Smith-Mundt Debate

February 9, 2013 § Leave a comment

Greetings from Washington. Along with the warmer temperatures and afternoon summer thunderstorms, a firestorm has erupted over a Congressional amendment related to U.S. public diplomacy. I put this post under Culture Posts, because the ferocity of the debate has had little to do with the technical aspects or merits of the legislation itself. At stake, and what the argument was really about, were iconic American values. The debate also reveals a surprising lack of understanding about just what is public diplomacy in the modern era of global communication. Indeed, rather than amending an old law, U.S. public diplomacy needs a new mindset.

At first the amendment seemed like a no-brainer update from the Smith-Mundt Act of 1948 to the Smith-Mundt Modernization Act of 2012. As the foundation of contemporary U.S. public diplomacy, there is a ton of background available on the original Smith-Mundt. A good running start is at Mountainrunner.us. The original legislation established the U.S. Information Agency with the mission of “informing and influencing foreign publics.” While the USIA has since been dissolved, the implicit understanding that public diplomacy targets “foreign publics”—not the domestic public—has remained a cornerstone assumption in U.S. public diplomacy practice and scholarship. Interestingly enough, numerous other countries assume the opposite—effective public diplomacy begins with the domestic public.

The reason the bill seemed like a no-brainer was because the Internet had made the distinction between foreign and domestic publics irrelevant and the bill effectively obsolete. Legally and philosophically, however … and this is where the debate takes off …

Anatomy of the Smith-Mundt Debate 2012

As is often the case when debates take on an outsized proportion there is usually buried symbolism. The raging battle on the surface is often a cover for issues that have deeper emotional significance. Trying to douse emotional flames with intellectual reason often only further fans the fire while submerging the original emotional triggers even deeper. Indeed, how the commentators spoke about the Amendment or tried to frame the issues only fueled the debate.

I decided to look take a closer look at the anatomy of the debate.

The debate grew exponentially in terms of quantity and intensity. On May 15, Representative Thornberry issued an 836-word press releaseannouncing the amendment (HR 5736). The first news article went out within hours. The battle of the blogs started on May 18 after a posting on Buzzfeed.com with the headline, “Congressmen Seek to Lift Propaganda Ban,” The Buzzfeed.com post not only changed the language from the original press release from public diplomacy to “propaganda,” but made it sound as if the reporter had obtained a news scoop rather than a press release—A sure tactic for generating interest among a wider audience.

Within a week, Technorati listed nearly 30 blog entries. Factivia.com had more than 60 entries on the topic. John Brown’s Public Diplomacy Review and Blog, perhaps the meeting ground for the debate, grew from one entry in third position on May 18, to more than 11 entries in a single day, to 54 entries totaling 16,642 words. And that was the first week. The original Buzzfeed.com post had gone viral with close to 200,000 views.

The debate grew in intensity. Bloggers on the right as well as the left attacked the amendment. Perhaps another indication that the debate was deeper than ideological differences was that opposition to it crossed the political spectrum. The emotionally charged language was similarly indicative. There was talk of “sock puppets” and “brain washing.” One prominent Progressive blogger warned of “the creeping fascism of American politics” that “would allow the Department of Defense to subject the U.S. domestic public to propaganda.” Suddenly, the military was included, which was not a far stretch but nevertheless inaccurate.

Adding to the debate were those trying to figure out what the fuss over “propaganda” was about. The word “propaganda” appeared to evoke a visceral response in older commentators, some who spoke from “personal experience.” For many younger commentators propaganda just seemed like another form of persuasion, which was reflected in their blog titles: “Propoganda? So What?” “Much ado about State Department ‘propaganda’“; “Dial back the outrage.” Again this happened from the liberal Mother Jones to the conservative The Blaze. The Blaze, which features a promo for the Tea Party movement on its video, actually switched its feelings about the amendment from “Disconcerting and Dangerous” to a roundtable history lesson by a panel of young commentators. They all had to read from their research notes and struggled to keep a straight face. (Video here)

To foreign observers, the Smith-Mundt debate may have looked rather confusing, if not odd. Public diplomacy scholar Robin Brown at Leeds University tweeted as much:

Robin Brown @rcmb: From outside the US Smith-Mundt domestic dissemination ban looks a bit odd. But apparently if you lift it US is doomed (May 20)

The intensity and speed with which the debate was spiraling suggested that the underlying, deeper issues at stake were significant. Indeed, the debate pitted two iconic American values against each other.

Appeal of the Future: Innovation & Opportunity

The very name of the bill – the Smith-Mundt Modernization Act of 2012 – resonates strongly and positively with future orientation that has long been a prized American value. Anthropologists have documented it. American politicians have catered to it. And, American immigrants who left the “old country” behind have embraced it. As a young nation, vision meant looking forward to the quest for the new, the improved, the opportunity for change, or the challenge of innovation. While there may be the tinge for nostalgia here and there, the appeal for Change and Hope (of the future) tend to triumph.

So, in the one corner, there is the appeal of future orientation. This explains the “history lessons” about Smith-Mundt as well as the references to “modern”, “advanced” communication technologies and the need to “update” or “modernize” the “obsolete” or “outdated” “decades-old” 1948 bill.

American Individualism

In the other corner is an even stronger American value orientation: individual freedom. If one peels back the language about “propaganda” it is about the fear of a loss of individual freedom and autonomy. The government will “take control,” the public will be “vulnerable” or “fall prey” to “brain washing” and other powerful forms of control.

If one looks closely, propaganda is often linked to an authoritarian or totalitarian regime, as was the case of the Thornberry press release. The anti-authoritarian appeal goes back to the American colonists and their rebellion against the King. Propaganda is also associated with deception, or more bluntly, lying by the authorities. Deliberate deception on the part of the government? Heaven forbid. America’s Founding Fathers built “checks and balances” into the foundation of the U.S. government structure. And lest the government forget its place, there are “the people” and of course, the “watch dog” press. While U.S. public diplomacy may be okay for “foreign” publics – including specifically targeting the youth of other countries, to expose the U.S. public to U.S. public diplomacy is a call to arms.

The images echo these iconic American values. There is the appeal to the modern, represented by technology. The image below was featured by the Mother Jones piece mocking the new “brainwashing” law.

Pitted against the fear of loss of individual freedom, are the images, albeit dated, of government “propaganda.”

The Smith-Mundt debate Illustrates how unexplored historical and cultural dynamics can have direct policy implications in public diplomacy. So long as the debate remains framed as a battle against two iconic cultural values – the appeal of the future versus the threat to individualism – the legislation may struggle.

Tomorrow, stay tuned for suggestions for cultural appeals that can reframe the debate for a new U.S. Public Diplomacy Act.

Blog from Culture Posts Series:

Zaharna, R. S. (June 6, 2012). “Culture Posts: Exposing The Battle of U.S. Values in the Smith-Mundt Debate,” in USC Center on Public Diplomacy, Blog Series

Culture Posts: Olympic Pageantry of Symbolism

July 16, 2012 § 4 Comments

As all eyes turn to London in the coming weeks for the Olympics, a pageantry of cultural symbolism will be on display for the culturally alert. Sometimes the most important messages in public diplomacy are the unspoken, symbolic ones. Anthropologist Edward T. Hall called it looking for the “eloquent cues.”

London may be the focus of public diplomacy attention and reap the greatest benefit. However, all countries are likely to seize and squeeze what public diplomacy mileage they can when the international spotlight shines in their direction. When you watch, watch for the cultural cues.

Color

One of the most prominent cultural cues resides in the selection and use of color. The significance of color begins with the Olympic symbol itself. The colors of the five interlocking circles –blue, yellow, black, green, red –against a white background contain the colors of the flags in the family of nations.

Color also plays a dominant symbolic role in the uniforms and dress of the athletes. During the Parade of Nations, one may find a stunning variety of national costumes but a clear pattern of close color parallels between what the athletes are wearing that the flag they are bearing. The team below is from Peru.

The parallel color theme between flag and dress carry over to the athletes’ uniforms. One can see the blue and gold flag of Sweden behind the group photo of its winning team.

Some athletes are literally are wrapped not only in the colors of their flag, but also the signature design. Members of the South African team will probably not be hard to identify in London.

In addition to being dressed in symbols of their countries, the host country may clad the athletes in additional Olympic touches. Athens, host of the 2004 summer Olympics, added the traditional wreath garlands for medal winners.

Uniforms

It is not just the color that makes the athletic uniforms or kits symbolic. Watch for the small national touches such as the Kalotaszegi folk motifs on this year’s Hungarian uniforms.

While such detail may be lost on the international community, to the home crowd they can carry enormous weight. The initial discontent among the American public with the U.S. team’s uniform was with the hat, which resembled a “French beret”.

Many suggested a cowboy hat or baseball cap would have been a better choice. The symbolism is not only on the outside. The inside tag revealed that the garment for U.S. team was “Made in China.” Another uproar ensued.

Aesthetic appeal is often related to what is culturally familiar as well as culturally prescribed.

This year the issue over what to wear has brought special attention to female athletes. And, here we get into some controversial territory when it comes to dress codes that require the covering – and uncovering – the female body.

In conducting research for this post, I was surprised by what I discovered. But then, when I remembered that international sports coverage is a multi-million dollar venture, perhaps I should not have been so surprised.

The various sports have their international committees that set the official dress regulations. Safety of the athletes has been a prime concern, hence the banning of scarves around the neck or long necklaces. However, how to dress the female athlete extends to the cultural.

Earlier this spring both the Badminton World Federation and the International Amateur Boxing Association introduced dress codes requiring female athletes to wear skirts or dresses. The rules were proposed “to improve the image of the sport and increase sponsorship.” Many athletes and critics called the new regulations “sexist.” The rules were dropped.

I was aware of the Islamic prescripts for female dress in public. “Modesty” is a fundamental principle in Islam that extends to words and action as well as dress. Many Muslim female athletes train and compete with their hair and body covered. In 2004, Roqaya Al Ghasara from Bahrain was the first to compete in Islamic dress. In 2008, she finished first in the women’s 200m sprint.

What I was unaware of was the dress regulations that required the exposure of female bodies. Up until this year, the International Volleyball Federation had a bikini rule in place: “Women must compete in bra-style tops and bikini bottoms that must not exceed six centimetres in width at the hip.”

Not coincidentally, Women’s Beach Volleyball is one of the highest rated women’s sports for viewers and among the most coveted tickets.

This year the rules were changed, according to officials, because countries had “religious and cultural requirements.” The Australian government has raised concerns of “sexploitation,”or the use of women’s bodies for marketing and media purpose. The new volleyball dress code allows for “shorts of a maximum length of three centimeters (1.18 inches) above the knee, and sleeved or sleeveless tops.”

Shorts are still short of full coverage. This causes problems for female athletes who are caught between Islamic codes requiring them to cover their bodies and the various sport dress codes requiring them to undercover their bodies. The Iranian Women’s Soccer team faced such a catch-22 situation and will not be able to participate because of the debate over their uniforms.

The debate over what female athletes wear – and cannot wear – does not appear to be about the sport competition, safety or their ability, but cultural ideas about what how best to dress the female body in public or for the camera.

Music

Music is also another broad area of cultural symbolism that runs throughout the Olympics. The national anthem is played during the awarding of medals for the individual athletes. The Olympics has its own hymn or official anthem.

Symbolism of the 2,008 drummers for the countdown of the 2008 summer Olympics in Beijing was one of the most memorable moments. It is still stunning to watch the video.

During the performance, the Chinese drummers chanted a phrase, “Welcome my friends.”

Gestures

Gestures are also highly symbolic. Kissing the gold may be a universal sign for the sweet reward of victory.

Perhaps the most powerful gestures however are not universal, but still recognizable. Again, what might be lost on the global audience can have a powerful political statement for the national public.

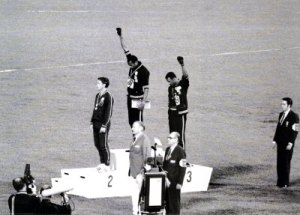

During the 1968 summer Olympics in Mexico – a time that coincided with the civil rights movement in America – two U.S. athletes raised their arms as a symbol of defiance black power and lower their heads as the U.S. anthem was played.

The Olympic games represent not just a public diplomacy opportunity for the host country. It is a pageantry of powerful symbols for all nations and participants. So when you’re watching, enjoy and keep an eye open for the many unspoken cues.

Social Media antithesis of Traditional Diplomacy?

May 21, 2012 § 1 Comment

Writing last week on Carnegie Endowment’s Digital Diplomacy forum, I called the social media the antithesis of diplomacy. I was speaking primarily about the clashing images – social media being fast and breaking things a la Fackbook’s motto and diplomacy moving slowly and cautiously. Wondering if the ambivalence of social media has more to do with what type of diplomacy we are referring to: (old) traditional diplomacy or (new) public diplomacy?

Both types of diplomacy, as the recent events between China and the US demonstrate over the Chinese dissident illustrate, are necessary. However, they operate using different communication methods and media. Traditional diplomacy, especially those aspects dealing with sensitive negotiations, place a premium on interpersonal communication. This preference for interpersonal contact may explain some of the resistance. Yet, while the new media may be the antithesis of traditional diplomacy, social media appears to be the requisite NEW tool for the NEW diplomacy.

For the new diplomat, or what Daryl Copeland calls the “guerrilla diplomat,” the front lines of diplomacy today have moved from the private, cosseted corridors of power to the people power of the streets.

“Today’s diplomatic encounters tend to take place publicly and cross-culturally: in a barrio or a souk, in an internet chat room or a blog, on main street or in a Quonset hut set astride the wire in a conflict zone.” — Daryl Copeland, Guerrilla Diplomacy

This new image of the people’s diplomat mirrors that described by U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in her Foreign Affairs piece last December. To operate effectively in such a rich social, public context requires new tools and approach. As Ambassador Sarukhan said during #digidiplomacy, diplomats now must be nimble, quick, and agile.

Yet, in using these new tools, diplomacy may be also further transformed. Communication tools are not neutral content vessels, but transform the user in the way that they are used. Hence, the significance of Ambassador Sarukhan’s follow-up observation on the move to atomization in diplomacy.

CarnegieEndow : @Arturo_Sarukhan: I think social media will atomize the authority, role, and profile of ambassadors and embassies #DigiDiplomacy

Rather than clashing, the new social media and the new public diplomat may be co-evolving – one shaping the other in 21st century diplomacy. As they evolve, rather than being leery of social media, public diplomats will have to become more skilled at incorporating and creatively expanding its relational, networking and collaborative public diplomacy capabilities.

The Ironies of Social Media in Public Diplomacy

May 20, 2012 § 1 Comment

Thursday morning I attended the discussion on “Digital Diplomacy: A New Era of Advancing Policy” at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington and on Twitter at #digidiplomacy. Carnegie had already posted video and audio of the event by early afternoon. USC PDC alumnus Matthew Wallin blogged his assessment of the discussion shortly there after.

Being the academic dinosaur that I am at heart, I came home typed up all my notes. Then, as an exercise to help me develop my social media skills, I compared my notes to the Twitter feed. @StephanieDahle, former journalist now at Brookings, has really mastered the medium. Good to study how she captured the idea without resorting to sqeezwrds.

My next step was to construct a theoretical framework around that comparison. Yes, I really am an academic.

And, having had the luxury of further scholarly reflection, I was struck by several ironies. Some of the ironies are captured in the tweets.

Irony #1: Social media — the antithesis of diplomacy?

Yesterday’s ambivalence about the use of social media was palatable. On the one hand, there was a sense of excitement. Martha Boudreau, of Fleishman-Hillard and co-sponsor of the event, opened by capturing the promise of what the buzz of new media is all about.

Boudreau shared some of the mind-numbing numbers on social media, but said its relevance to diplomacy goes beyond numbers. For Mexico’s Ambassor Arturo Sarukhan, social media was not just about relevancy, social media was a necessity. He shared his adaptation of an old Mexican saying to underscore his point. It used to be, “If you moved, you were not in the picture.” He up-dated that saying for Twitter:

@colehutch: #digidiplomacy “if you don’t tweet, you are not in the photograph.” meaning if you aren’t using social, you aren’t relevant diplomatically

On the one hand, there was excitement. Like the new toy on the block, all the kids are asking, What is it? Can I play with it too?

Then, on the other hand, there was the wariness. Alert to the apprehension, or perhaps skepticism, the panelists seemed on the defensive from the get go. Alec Ross, the guru of social media @State and first of the panelist to speak, immediately introduced what became the mantra echoed among the discussants: “social media is a TOOL.” He emphasized that by saying he was a Medieval History major. He wasn’t interested in technology, but in advancing policy interests. Using social media was a tool for advancing policy interests.

All the panelists repeated the mantra at least once or twice each time they spoke: “social media is a TOOL.” Nevertheless, the very first question from the audience was a not so much a question but a statement about the failings of social medial as a substitute for personal contact in diplomacy.

Why the mantra of “social media as a tool” may fail to resonant or have difficulty taking hold with the diplomatic community may be because of the contrasting images of social media as a tool of the fast and furious and the image of diplomacy in unhurried lap of pearls and dark suits. Both images may need updating or refocusing. However, the contrasting images that linger were captured in a statement by a panelist and a reflective observation by the discussion moderator.

“Another motto at Facebook: ‘Move fast and break things.” —

@Sarah Wynn-Williams of@facebook, former New Zealand diplomat and current manager of public policy at Facebook

To which, Tom Carver of the Carnegie Endowment, who was moderating the discussion observed: “That’s the opposite of what diplomacy is: “Move slow and be careful not to break anything.”

Viewed in this light, the ambivalence of social media makes sense. Social media could be seen as the antithesis of diplomacy.

Irony #2: Social media — promoting anti-social behavior?

Since its debut, everyone has talked about how the new media was so personal. How it connects everyone. How, well, how social the social media is. The name even changed from new media to social media. Yesterday, it was digital media. And the some of the stark reality of social media came out in a rather surprising remark by Alec Ross. It became a top tweet and re-tweet.

@StephanieDahle “Social media tends to punish moderation” – @AlecJRoss #DigiDiplomacy

Ross made the comment in the context of speaking about the tension between representative democracy (i.e, Congress) and direct democracy, or citizen using social media to make their voices heard. Ross remarked, “Social media punishes moderation – those who seek compromise – and amplifies extremism on both ends.”

On the surface, that sounds true. In a crowded platform, the extreme voices stand out. They get the visibility or listened to. Moderate voices are easily drowned out. Several researchers have been studying how the media tools/conventions are contributing to a more polarized atmosphere in U.S. politics.

Which, going back to diplomacy, may be another reason to be leery of social media. If diplomacy about building relations, compromise and accommodation to others is at the core. Also, compromise and learning to modify one’s behavior in relation to others is at the core of social behavior. Also, while moderate voices may be easily drowned out, they nevertheless tend to resonate with the widest audience. How ironic it would be if social media is promoting anti-social, uncompromising behavior.

Having pondered these ironies, I am now the more curious about social media’s evolving role/s in public diplomacy. Yes, Phil Seib, your new book on social media and public diplomacy is next on my reading list.

====

For an interesting study on the emergence of new media phenomena with the mass media, see Diana Mutz “How the Mass Media Divides Us,” from Red and Blue Nation, edited by D. Brady and P. Divola (Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2007. Publisher URL: http://www.brookings.edu/press.aspx

For more recent collection of studies on assessment of social media in international political contexts special issue of Journal of Communication (April 2012) edition by Philip Howard and Malcolm Parks, “Social Media and Political Change: Capacity, Constraint, and Consequence.”

* Blog originally published on USC Center for Public Diplomacy Blog Roll.

Connecting Dots – Tara, Policies and People

April 26, 2012 § 1 Comment

For some time I’ve been contemplating how to connect the dots in public diplomacy. In an interconnected world, most everything is connected. Since class for the semester finished last night, let me try my hand with observations for this week.

I’ll start with the dinner for Tara Sonenshine on the eve before her swearing in ceremony as the new U.S. Undersecretary of State for Public Diplomacy. Seems like I had been hearing about “Tara” for weeks. The first name basis everyone was using appeared to capture her spirit. She entered the room with a burst of energy, enthusiasm. Very personable. And, definitely ready to go, which is exactly what she will need.

Which brings me to the first link in connecting the dots this week. On the same day that John Brown’s PD blog carried the full text of Tara’s remarks at her swearing-in ceremony, including the great quote: “Policy is about people. Without a deeper understanding of foreign publics, our policies are just flying blind” …

… there was Al-Jazeera news lineup featuring the Arabic translation of James Petras’ book, Arab Revolt and the Imperialist Counterattack.

The combination of Petras’ credentials (distinguished academic, 64 books, etc.) and the book’s theme of the U.S. track record of supporting unpopular dictators who support US interests are formidable. Petras made a compelling case for U.S. underhanded and confused efforts to protect its interests over the interests of the people. The article shared the book’s highlights with point by point clarity. Two dots that just made Tara’s job a little harder.

Another dot to connect to the theme of counter American narratives to the US public diplomacy narrative is van Buren’s book We Meant Well. While the style of Van Buren’s writing is entertaining, his message is sobering. When it comes to winning hearts and minds, the real audience doesn’t appear to be skeptical foreign publics — who are all too aware of the situation on ground. Instead, it’s the policy makers back in Washington who want results and who control the budgetary purse string. On-the-ground realities versus Washington realities. Public diplomacy gets caught in the middle.

The immediate reaction may be to try to isolate and discredit these and other works that tarnish the U.S. image, sully U.S. policies and make U.S. public diplomacy efforts that much harder. That’s normal, understandable and a short term option. In the long term, it may not be the optimal solution for addressing U.S. public diplomacy’s perennial woes with certain publics.

What I personally like about Tara’s original quote is the idea that people do matter in U.S. policy. In U.S. public diplomacy “foreign publics” often seem as abstract as the goal of “informing, influencing and engaging.” However at the people level, it is not that abstract or complex. When people are negatively affected by U.S. policies, U.S. public diplomacy suffers. U.S. policies communicate.

This was the critical lesson in Battles to Bridges. A major failing in the U.S. grand strategy of U.S. public diplomacy was that it tried to separate U.S. communication strategies from U.S. policies. When U.S. public diplomacy failed it was not the policies, but the communication strategies — or those responsible for communicating the policies.

Trying to operate in today’s environment using an intransigent, rather than an integrative grand strategy sets the new U.S. public diplomacy head in the same position as her predecessors.

If Tara can bring her policy-people message or even the more basic message that “Policy communicates” to U.S. policy makers and begin to integrate public diplomacy into the policy realm, she will have a greater chance of disconnecting the dots that damage U.S. public diplomacy. And, her tenure will likely be stronger and longer.